Transformation

Throughout Advent, we have reflected on a three-fold process of pilgrimage akin to the phases of walking a labyrinth: setting our intention, or walking in, encounter with the Holy, akin to the union of the center, and making meaning of our experiences and integrating them into our lives, or walking out. The topic of our fourth reflection, transformation, is not a phase of pilgrimage, but its result. Like encounter, transformation is not something we do or control; it is God’s work. The theological concept of sanctification describes this work of the Holy Spirit within the soul of a baptized person: theologian Michael Horton, in his book The Christian Faith: A Systematic Theology for Pilgrims on the Way, defines sanctification as “an ongoing work within believers that renews them inwardly and conforms them gradually to the image of God in Christ.”

That is to say that, when we set out on the pilgrim path, be it for a season or for a lifetime, we do not end that journey the same as when we started. Somewhere along the way, or perhaps with each step, things shifts in us, until we begin to see, walk, live in a whole new way. Burdens may fall away, or our legs grow stronger, we know not which, but we notice at some point that our step is lighter on the path. Like the sun breaking through the clouds, joy appears and floods our hearts. We return home with the knowledge that nothing will ever be the same.

Becoming Pilgrims

Our journey to Canterbury came early, being our second stop after a ten-day stay in Oxfordshire. Before we left the village of Bampton, which we had fallen in love with, my eldest confided some homesickness to me. We still had five weeks to go! Canterbury had been a later addition to the itinerary. I had been there before, but the thought, “How can an Episcopal priest go on sabbatical to England and not go to the seat of the Anglican Communion?” nagged, so I fit it in. No casual stopover, it definitely fit the demands of “intention,” as we had to drive across half the width of England to get there, and then the entire width of the fattest part of the island to get to our next stop in Cornwall. We had thirty hours in Canterbury, and I did not have any expectations to speak of. But Canterbury transformed us. The children had resolutely refused to consider our family “tourists,” insisting instead that we were “visitors.” We may have arrived in Canterbury as visitors, but we left as pilgrims.

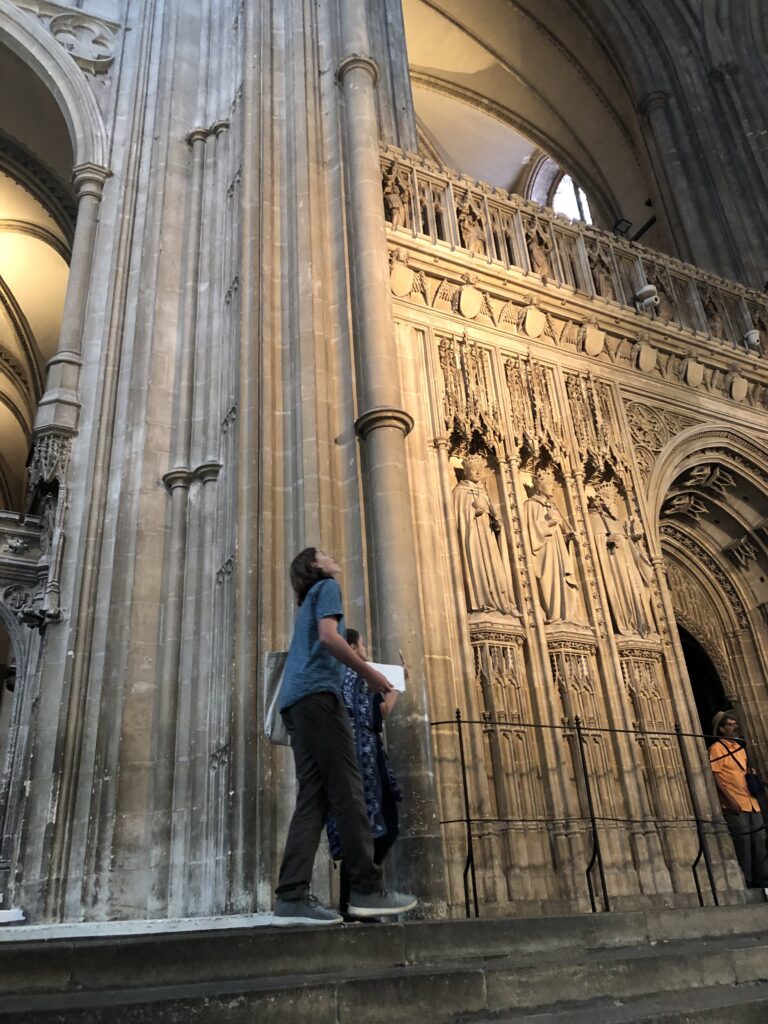

We had rented an AirBnB on the King’s Mile, which felt like a modern muggle Diagon Alley (apologies to non-Harry Potter fans!) We were immediately enchanted by the winding Tudor streets and the view of the sunset over the cathedral, towering over it all, from our third-floor window. The next day, our only full day in the city, my eldest and I made our way to the cathedral for 7:30 morning prayer followed by Eucharist. Telling the guard at the gate that we were there for morning prayer felt like offering a secret password— tourist hours and prayer hours are kept strictly separate. The lawns were being replaced for the arrival of close to 700 bishops from around the Anglican Communion for the Lambeth Conference, and we were hit by the sprinklers as we entered the side door and descend to the crypt. There we gathered with around thirty people for prayer, finding my colleague from Northern California who was basing his sabbatical in Canterbury. After a couple of minutes of book juggling, we settled into the rhythm of the prayer. The morning light streaming through the stained-glass windows settled into my soul as the words of scripture did. When the celebration had ended, we were invited out for breakfast with my friend and a group of locals, getting a tour of the grounds from a long-time Cathedral member on the way out. It included a description of the German bombing during WWII.

Our official guided tour later in the day turned up more treasures— we were shown a small chapel in the crypt which had been walled off during an early phase of remodeling and only uncovered in the 1940’s. It contained untouched medieval wall paintings, the like of which had, before they were whitewashed during the iconoclastic Reformation, had covered the walls of every worship space in England to illustrate the stories of scripture for the illiterate. My eldest marveled and madly sketched, while my middle son took a more embodied approach. He was selected by the guide to take the abbot’s seat in the great hall of the monastic chapter, and quickly went to his knees to reverently ascend the last steps to where Thomas Beckett’s shrine had stood, just as medieval pilgrims would have done. I was moved to learn that, when the pilgrims’ shrines were being destroyed by the soldiers of Henry VIII during the Reformation, the monks had spirited away the remains of their saint— no one knew where. It is likely that they reinterred Thomas Beckett’s bones in various places around the cathedral. “How wonderful…” I thought, “Instead of this one spot being made holy by the remains of this holy man, now the whole place is his shrine.”

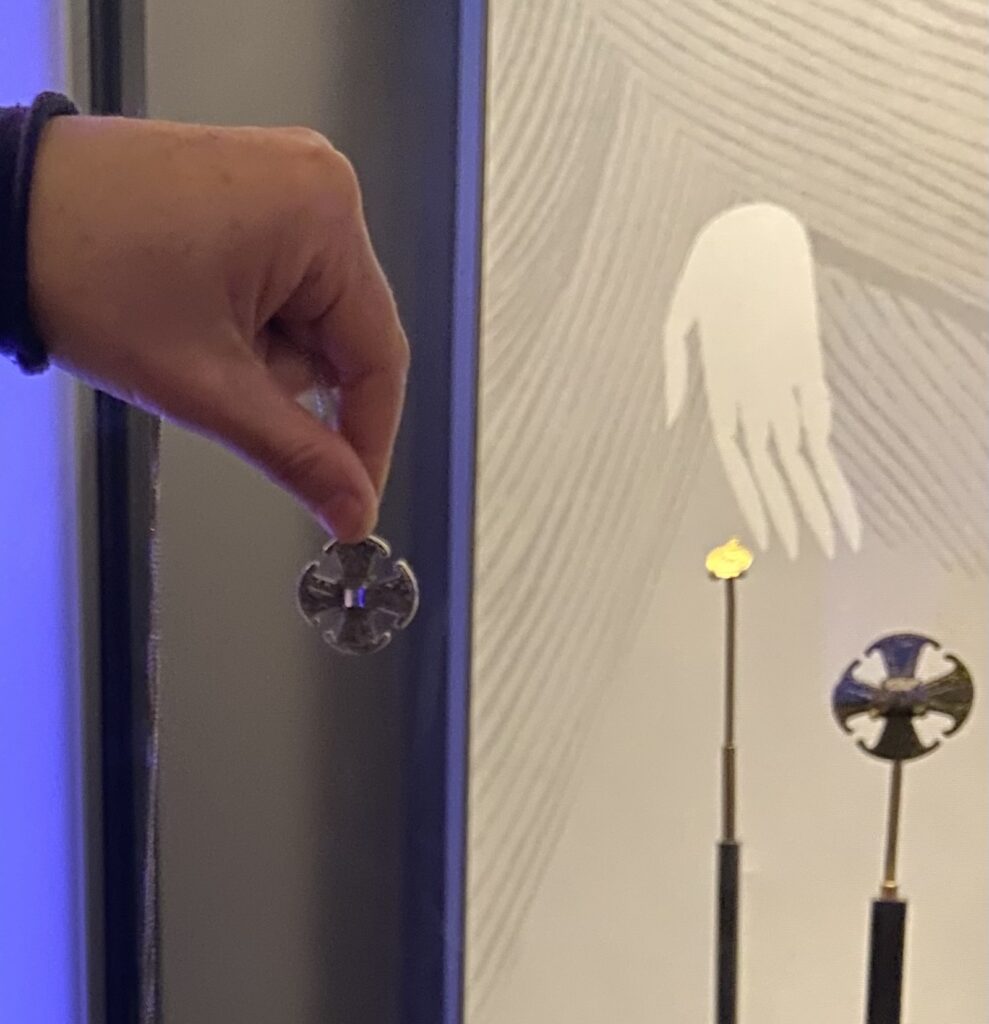

Canterbury gave gift upon gift, and we had so little time to soak it all in. The last gift came just an hour before we left. For my ordination 17 years before, my mentors, a married couple who were both priests, gave me a beautiful Canterbury cross they had purchased on their sabbatical to England. It is a replica of a Saxon cross dug up from a street in Canterbury in the 19th century. I had dearly wanted to see the 1,200 year old original, but the museum which housed it closed before we had a chance to get there. In a few precious moments after our second morning Eucharist, through the graciousness of a guard who let me look around even though it was not tourist hours, I found the original in a special exhibit in the back of the crypt, on loan from the museum to the cathedral. I placed my own cross in the baptismal font before I left, and into every body of holy water I encountered until the end of our pilgrimage. My Canterbury cross, which had always before felt somehow too beautiful and special for me, became my own, and synonymous with my pilgrimage.

Joseph’s Transformation

The gospel for this fourth Sunday of Advent, the birth narrative from Matthew, is all about transformation. In Matthew, Jesus’ birth takes place quietly and simply, with no angel chorus or shepherds’ homage, as in Luke. But if we listen closely we can hear the undercurrents of tension and revelation in the story. Joseph, presumably devastated to learn that Mary is pregnant and knowing he is not the father, resolves to separate from her, but is visited by an angel in a dream who tells him the true state of affairs and the nature of this child. Joseph’s world is transformed. The drama will build later in the second chapter of Matthew, which involves the machinations of King Herod and the journey of the magi, and three more angelic visitations with instructions to Joseph, all of which he wordlessly carries out to the letter. These instructions take them to far-away Egypt, and then finally to settle in Nazareth, where Jesus will be brought up. Joseph’s previous life was about himself. While a righteous man, Matthew tells us, Jospeh could only see from his own perspective, from his own desires and his own life. God’s messengers transform Joseph’s understanding, and his life is no longer his own. His whole life becomes dedicated to the protection of this child and his mother, following the divine directive. Joseph will never be the same. After the incarnation of the eternal Word into human flesh in the baby Joseph protects, the world will never be the same either.

Practices

Our Advent pilgrimage toward incarnation is about allowing that transformation of perspective and of what our lives are about to take place in our own hearts as well. In The Art of Pilgrimage, Phil Cousineau writes, “Pilgrimage is the kind of journeying that marks… [a] move from mindless to mindful, soulless to soulful travel. The difference may be subtle or dramatic; by definition it is life-changing.” He continues, “A bona fide pilgrimage may mean becoming more conscious about yourself and the world… but it needs to bring about a change of mind, a shift in the soul. No change, no pilgrimage.” In other words, the proof of pilgrimage is in the pudding.

This work of transformation belongs to God, and, as one mystic has observed, what God is doing in my soul is really none of my business! Nevertheless, a few practices may prove helpful in participating in the Spirit’s work of transformation in our lives.

Release is very similar to the spiritual practice of acceptance/surrender I spoke of in the encounter phase; notice that these both have their place in a phase where the primary action belongs to God! Release, of course, is simply letting go. Simple, but not easy. Begin in a state of quiet contemplation, after a few minutes of silence, by asking yourself: “What do I need to let go of?” Aspirations, desires, worries, resentments, expectations… allow the Spirit to show you in silence what you, like Joseph, are called to let go of. You can visualize these, like burdens, simply dropping to the ground, or perhaps sinking into the ocean. A physical manifestation of this can be very helpful— writing them down, and placing them in a container with a lid. Perhaps burning them when the time is right. Writing them on dissolving paper and then stirring them into water can be very satisfying! You may need to release something multiple times before you can feel that you are truly free of it. Remember that even this work of release is God’s work, but our desire is a key part of the process.

Celebration has been key for me in recognizing and rejoicing in Gods’ work of transformation. With the transformation of months of healing and the sabbatical pilgrimage, I find myself in a drastically different place, like night and day, from where I was last fall. The season and everything that goes with it, like a memory marker, takes me back to where I was a year ago (and all the years before that). As my mind and heart bring me glimpses of what life was like before, I can see and marvel anew at the transformation God has wrought in my life. I have the ability to be in the present moment now. I have a durable peace. I have joy. Seeing that stark difference, joy bubbles up upon joy, and I can proclaim with the psalmist, “Great things are they that you have done, O Lord my God! How great your wonders and your plans for us! There is none who can be compared with you.” (Psalm 40:5, BCP)

To engage celebration, reflect on different moments of your journey, perhaps Advents and Christmases past. What was it like for you in this place on your last journey around the sun? What might future Christmases look like (to borrow from Dickens)? What changes do you notice that you can celebrate? What changes do you desire that you can ask for? Can you celebrate in the faith that God is doing better things for you than you can even ask for or imagine?

Gift-giving as gratitude. In The Art of Pilgrimage, Cousineau talk about the custom of pilgrims traveling with small gifts or offerings. These might be left at the holy place to which the pilgrim is journeying, or be given to those who show the pilgrim hospitality along the way. In either case, the gifts the pilgrims offers are gifts of gratitude. Gift-giving this time of year can easily become just another task to cross off the long list of December activities. Could we create the spiritual space to see each gift we give other as, instead of a rote, obligatory exchange, a gift of gratitude for that person’s presence in our lives? Or even a gratitude-offering to God for the gift of our lives? As you shop, as you wrap, as you give, ask for the holy to transform this experience. Ask for the gift of gratitude.

The first week of October each year, with a group of Episcopal clergy, I take a challenging hike known as the St. Francis Pilgrimage. This year, I learned this saying from one of our sage company:

If you don’t journey but change, you are a chameleon.

If you journey but don’t change, you are a tourist.

If you journey and change you, are a pilgrim.

May God, through our Advent journey, give the grace of transformation, and make us true pilgrims. And may we, with the psalmist declare, “You have restored us, O Lord God of hosts, you have shown the light of your countenance, and we are saved.” (Paraphrase of Psalm 80:18, BCP)

Prayer

Creator of the world, you are the potter, we are the clay, and you form us in your own image: Shape our spirits by Christ’s transforming power, that as one people we may live out your compassion and justice, whole and sound in the realm of your peace. Amen.

From Daily Prayer for All Seasons

Poem

Messenger

My work is loving the world.

Here the sunflowers, there the hummingbird—

equal seekers of sweetness.

Here the quickening yeast; there the blue plums.

Here the clam deep in the speckled sand.

Are my boots old? Is my coat torn?

Am I no longer young, and still not half-perfect?

Let me keep my mind on what matters,

Which is my work.

Which is mostly standing still

and learning to be astonished.

The phoebe, the delphinium.

The sheep in the pasture, and the pasture.

Which is mostly rejoicing, since all the ingredients are here,

Which is gratitude, to be given a mind and a heart

and these body-clothes,

a mouth with which to give shouts of joy

to the moth and the wren, to the sleepy dug-up clam,

telling them all, over and over, how it is

that we live forever.

-Mary Oliver

Your 4 meditations have been a huge blessing to me. They are beautifully written, and I can hear the Holy Spirit coming through. Thank you so sharing them with us. May God continue to bless you in your most important work in getting through to us. With much love.